| “The Gift of the Magi”

is a classic Christmas tale by O. Henry about a

young couple who each sells a precious possession to

buy a gift for the other. This is the complete text

of O’Henry’s short story, The Gift of the Magi, as

provided by

Project Gutenberg.

The

Gift of the Magi

ONE dollar and eighty-seven

cents. That was all. And sixty cents of it was in

pennies. Pennies saved one and two at a time by

bulldozing the grocer and the vegetable man and the

butcher until one’s cheeks burned with the silent

imputation of parsimony that such close dealing

implied. Three times Della counted it. One dollar

and eighty-seven cents. And the next day would be

Christmas.

There was clearly nothing to

do but flop down on the shabby little couch and

howl. So Della did it. Which instigates the moral

reflection that life is made up of sobs, sniffles,

and smiles, with sniffles predominating.

While the mistress of the

home is gradually subsiding from the first stage to

the second, take a look at the home. A furnished

flat at $8 per week. It did not exactly beggar

description, but it certainly had that word on the

lookout for the mendicancy squad.

In the vestibule below was a

letter-box into which no letter would go, and an

electric button from which no mortal finger could

coax a ring. Also appertaining thereunto was a card

bearing the name “Mr. James Dillingham Young.”

The “Dillingham” had been

flung to the breeze during a former period of

prosperity when its possessor was being paid $30 per

week. Now, when the income was shrunk to $20,

though, they were thinking seriously of contracting

to a modest and unassuming D. But whenever Mr. James

Dillingham Young came home and reached his flat

above he was called “Jim” and greatly hugged by Mrs.

James Dillingham Young, already introduced to you as

Della. Which is all very good.

Della finished her cry and

attended to her cheeks with the powder rag. She

stood by the window and looked out dully at a gray

cat walking a gray fence in a gray backyard.

Tomorrow would be Christmas Day, and she had only

$1.87 with which to buy Jim a present. She had been

saving every penny she could for months, with this

result. Twenty dollars a week doesn’t go far.

Expenses had been greater than she had calculated.

They always are. Only $1.87 to buy a present for

Jim. Her Jim. Many a happy hour she had spent

planning for something nice for him. Something fine

and rare and sterling-something just a little bit

near to being worthy of the honor of being owned by

Jim.

There was a pier glass

between the windows of the room. Perhaps you have

seen a pier glass in an $8 flat. A very thin and

very agile person may, by observing his reflection

in a rapid sequence of longitudinal strips, obtain a

fairly accurate conception of his looks. Della,

being slender, had mastered the art.

Suddenly she whirled from

the window and stood before the glass. Her eyes were

shining brilliantly, but her face had lost its color

within twenty seconds. Rapidly she pulled down her

hair and let it fall to its full length.

Now, there were two

possessions of the James Dillingham Youngs in which

they both took a mighty pride. One was Jim’s gold

watch that had been his father’s and his

grandfather’s. The other was Della’s hair. Had the

queen of Sheba lived in the flat across the

airshaft, Della would have let her hair hang out the

window some day to dry just to depreciate Her

Majesty’s jewels and gifts. Had King Solomon been

the janitor, with all his treasures piled up in the

basement, Jim would have pulled out his watch every

time he passed, just to see him pluck at his beard

from envy.

So now Della’s beautiful

hair fell about her rippling and shining like a

cascade of brown waters. It reached below her knee

and made itself almost a garment for her. And then

she did it up again nervously and quickly. Once she

faltered for a minute and stood still while a tear

or two splashed on the worn red carpet.

On went her old brown

jacket; on went her old brown hat. With a whirl of

skirts and with the brilliant sparkle still in her

eyes, she fluttered out the door and down the stairs

to the street.

Where she stopped the sign

read: “Mme. Sofronie. Hair Goods of All Kinds.” One

flight up Della ran, and collected herself, panting.

Madame, large, too white, chilly, hardly looked the

“Sofronie.”

“Will you buy my hair?”

asked Della.

“I buy hair,” said Madame.

“Take yer hat off and let’s have a sight at the

looks of it.”

Down rippled the brown

cascade.

“Twenty dollars,” said

Madame, lifting the mass with a practised hand.

“Give it to me quick,” said

Della.

Oh, and the next two hours

tripped by on rosy wings. Forget the hashed

metaphor. She was ransacking the stores for Jim’s

present.

She found it at last. It surely had been made

for Jim and no one else. There was no other like it

in any of the stores, and she had turned all of them

inside out. It was a platinum fob chain simple and

chaste in design, properly proclaiming its value by

substance alone and not by meretricious

ornamentation-as all good things should do. It was

even worthy of The Watch. As soon as she saw it she

knew that it must be Jim’s. It was like him.

Quietness and value-the description applied to both.

Twenty-one dollars they took from her for it, and

she hurried home with the 87 cents. With that chain

on his watch Jim might be properly anxious about the

time in any company. Grand as the watch was, he

sometimes looked at it on the sly on account of the

old leather strap that he used in place of a chain.

When Della reached home her

intoxication gave way a little to prudence and

reason. She got out her curling irons and lighted

the gas and went to work repairing the ravages made

by generosity added to love. Which is always a

tremendous task, dear friends-a mammoth task.

Within forty minutes her

head was covered with tiny, close-lying curls that

made her look wonderfully like a truant schoolboy.

She looked at her reflection in the mirror long,

carefully, and critically.

“If Jim doesn’t kill me,”

she said to herself, “before he takes a second look

at me, he’ll say I look like a Coney Island chorus

girl. But what could I do-oh! what could I do with a

dollar and eighty-seven cents?”

At 7 o’clock the coffee was

made and the frying-pan was on the back of the stove

hot and ready to cook the chops.

Jim was never late. Della

doubled the fob chain in her hand and sat on the

corner of the table near the door that he always

entered. Then she heard his step on the stair away

down on the first flight, and she turned white for

just a moment. She had a habit of saying a little

silent prayer about the simplest everyday things,

and now she whispered: “Please God, make him think I

am still pretty.”

The door opened and Jim

stepped in and closed it. He looked thin and very

serious. Poor fellow, he was only twenty-two-and to

be burdened with a family! He needed a new overcoat

and he was without gloves.

Jim stopped inside the door,

as immovable as a setter at the scent of quail. His

eyes were fixed upon Della, and there was an

expression in them that she could not read, and it

terrified her. It was not anger, nor surprise, nor

disapproval, nor horror, nor any of the sentiments

that she had been prepared for. He simply stared at

her fixedly with that peculiar expression on his

face.

Della wriggled off the table

and went for him.

“Jim, darling,” she cried,

“don’t look at me that way. I had my hair cut off

and sold because I couldn’t have lived through

Christmas without giving you a present. It’ll grow

out again-you won’t mind, will you? I just had to do

it. My hair grows awfully fast. Say ‘Merry

Christmas!’ Jim, and let’s be happy. You don’t know

what a nice-what a beautiful, nice gift I’ve got for

you.”

“You’ve cut off your hair?”

asked Jim, laboriously, as if he had not arrived at

that patent fact yet even after the hardest mental

labor.

“Cut it off and sold it,”

said Della. “Don’t you like me just as well, anyhow?

I’m me without my hair, ain’t I?”

Jim looked about the room

curiously.

“You say your hair is gone?”

he said, with an air almost of idiocy.

“You needn’t look for it,”

said Della. “It’s sold, I tell you-sold and gone,

too. It’s Christmas Eve, boy. Be good to me, for it

went for you. Maybe the hairs of my head were

numbered,” she went on with sudden serious

sweetness, “but nobody could ever count my love for

you. Shall I put the chops on, Jim?”

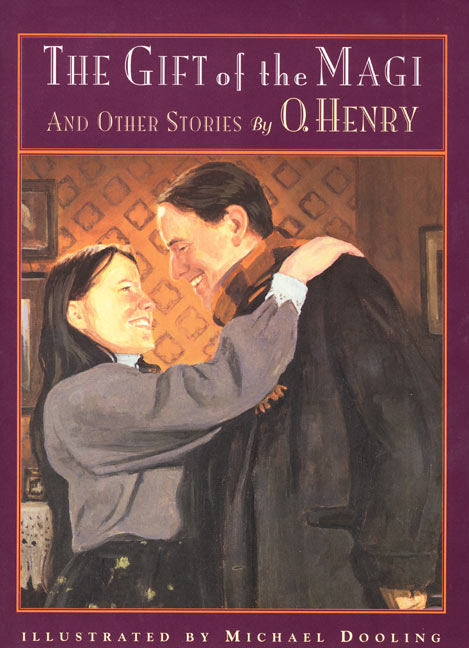

Out of his trance Jim seemed

quickly to wake. He enfolded his Della. For ten

seconds let us regard with discreet scrutiny some

inconsequential object in the other direction. Eight

dollars a week or a million a year-what is the

difference? A mathematician or a wit would give you

the wrong answer. The magi brought valuable gifts,

but that was not among them. This dark assertion

will be illuminated later on.

Jim drew a package from his

overcoat pocket and threw it upon the table.

“Don’t make any mistake,

Dell,” he said, “about me. I don’t think there’s

anything in the way of a haircut or a shave or a

shampoo that could make me like my girl any less.

But if you’ll unwrap that package you may see why

you had me going a while at first.”

White fingers and nimble

tore at the string and paper. And then an ecstatic

scream of joy; and then, alas! a quick feminine

change to hysterical tears and wails, necessitating

the immediate employment of all the comforting

powers of the lord of the flat.

For there lay The Combs-the

set of combs, side and back, that Della had

worshipped long in a Broadway window. Beautiful

combs, pure tortoise shell, with jewelled rims-just

the shade to wear in the beautiful vanished hair.

They were expensive combs, she knew, and her heart

had simply craved and yearned over them without the

least hope of possession. And now, they were hers,

but the tresses that should have adorned the coveted

adornments were gone.

But she hugged them to her

bosom, and at length she was able to look up with

dim eyes and a smile and say: “My hair grows so

fast, Jim!”

And then Della leaped up

like a little singed cat and cried, “Oh, oh!”

Jim had not yet seen his

beautiful present. She held it out to him eagerly

upon her open palm. The dull precious metal seemed

to flash with a reflection of her bright and ardent

spirit.

“Isn’t it a dandy, Jim? I

hunted all over town to find it. You’ll have to look

at the time a hundred times a day now. Give me your

watch. I want to see how it looks on it.”

Instead of obeying, Jim

tumbled down on the couch and put his hands under

the back of his head and smiled.

“Dell,” said he, “let’s put

our Christmas presents away and keep ‘em a while.

They’re too nice to use just at present. I sold the

watch to get the money to buy your combs. And now

suppose you put the chops on.”

The magi, as you know, were

wise men-wonderfully wise men-who brought gifts to

the Babe in the manger. They invented the art of

giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts

were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the

privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And

here I have lamely related to you the uneventful

chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most

unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest

treasures of their house. But in a last word to the

wise of these days let it be said that of all who

give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who

give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest.

Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.

|